Retry pattern

Need(s)

Services collaborate when handling one client request. When one service invokes another one, a failure may occur because of transient faults. Transient Faults can be the momentary loss of network connectivity to components and services for example, the temporary unavailability of a service, or timeouts that occur when a service is busy. These faults are typically self-correcting, and if the action that triggered a fault is repeated after a suitable delay it's likely to be successful.

Retry pattern definition

Transient faults aren't uncommon especially in cloud environment and an application should be designed to handle them elegantly and transparently. This minimizes the effects faults can have on the business tasks the application is performing. If an application detects a failure when it tries to send a request to a remote service, it can handle the failure using the following strategies:

Cancel: If the fault indicates that the failure isn't transient or is unlikely to be successful if repeated, the application should cancel the operation and report an exception. For example, an authentication failure caused by providing invalid credentials is not likely to succeed no matter how many times it's attempted.

Retry: If the specific fault reported is unusual or rare, it might have been caused by unusual circumstances such as a network packet becoming corrupted while it was being transmitted. In this case, the application could retry the failing request again immediately because the same failure is unlikely to be repeated and the request will probably be successful.

Retry after delay: If the fault is caused by one of the more commonplace connectivity or busy failures, the network or service might need a short period while the connectivity issues are corrected or the backlog of work is cleared. The application should wait for a suitable time before retrying the request.

For the more common transient failures, the period between retries should be chosen to spread requests from multiple instances of the application as evenly as possible. This reduces the chance of a busy service continuing to be overloaded. If many instances of an application are continually overwhelming a service with retry requests, it'll take the service longer to recover.

If the request still fails, the application can wait and make another attempt. If necessary, this process can be repeated with increasing delays between retry attempts, until some maximum number of requests have been attempted. The delay can be increased incrementally or exponentially, depending on the type of failure and the probability that it'll be corrected during this time.

Issues and considerations

We should consider the following points when deciding how to implement the retry pattern. The retry policy should be tuned to match the business requirements of the application and the nature of the failure. For some noncritical operations, it's better to fail fast rather than retry several times and impact the throughput of the application. For example, in an interactive web application accessing a remote service, it's better to fail after a smaller number of retries with only a short delay between retry attempts, and display a suitable message to the user (for example, “please try again later”). For a batch application, it might be more appropriate to increase the number of retry attempts with an exponentially increasing delay between attempts.

An aggressive retry policy with minimal delay between attempts, and a large number of retries, could further degrade a busy service that's running close to or at capacity. This retry policy could also affect the responsiveness of the application if it's continually trying to perform a failing operation.

If a request still fails after a significant number of retries, it's better for the application to prevent further requests going to the same resource and simply report a failure immediately. When the period expires, the application can tentatively allow one or more requests through to see whether they're successful.

Consider whether the operation is idempotent. If so, it's inherently safe to retry. Otherwise, retries could cause the operation to be executed more than once, with unintended side effects. For example, a service might receive the request, process the request successfully, but fail to send a response. At that point, the retry logic might re-send the request, assuming that the first request wasn't received.

A request to a service can fail for a variety of reasons raising different exceptions depending on the nature of the failure. Some exceptions indicate a failure that can be resolved quickly, while others indicate that the failure is longer lasting. It's useful for the retry policy to adjust the time between retry attempts based on the type of the exception.

Consider how retrying an operation that's part of a transaction will affect the overall transaction consistency. Fine tune the retry policy for transactional operations to maximize the chance of success and reduce the need to undo all the transaction steps.

Ensure that all retry code is fully tested against a variety of failure conditions. Check that it doesn't severely impact the performance or reliability of the application, cause excessive load on services and resources, or generate race conditions or bottlenecks.

Implement retry logic only where the full context of a failing operation is understood. For example, if a task that contains a retry policy invokes another task that also contains a retry policy, this extra layer of retries can add long delays to the processing. It might be better to configure the lower-level task to fail fast and report the reason for the failure back to the task that invoked it. This higher-level task can then handle the failure based on its own policy.

It's important to log all connectivity failures that cause a retry so that underlying problems with the application, services, or resources can be identified.

Investigate the faults that are most likely to occur for a service or a resource to discover if they're likely to be long lasting or terminal. If they are, it's better to handle the fault as an exception. The application can report or log the exception, and then try to continue either by invoking an alternative service (if one is available), or by offering degraded functionality. For more information on how to detect and handle long-lasting faults.

When to use it or not ?

Use this pattern when an application could experience transient faults as it interacts with a remote service or accesses a remote resource. These faults are expected to be short lived, and repeating a request that has previously failed could succeed on a subsequent attempt. This pattern might not be useful:

- When a fault is likely to be long lasting, because this can affect the responsiveness of an application. The application might be wasting time and resources trying to repeat a request that's likely to fail.

- For handling failures that aren't due to transient faults, such as internal exceptions caused by errors in the business logic of an application.

- As an alternative to addressing scalability issues in a system. If an application experiences frequent busy faults, it's often a sign that the service or resource being accessed should be scaled up.

Integration with other patterns

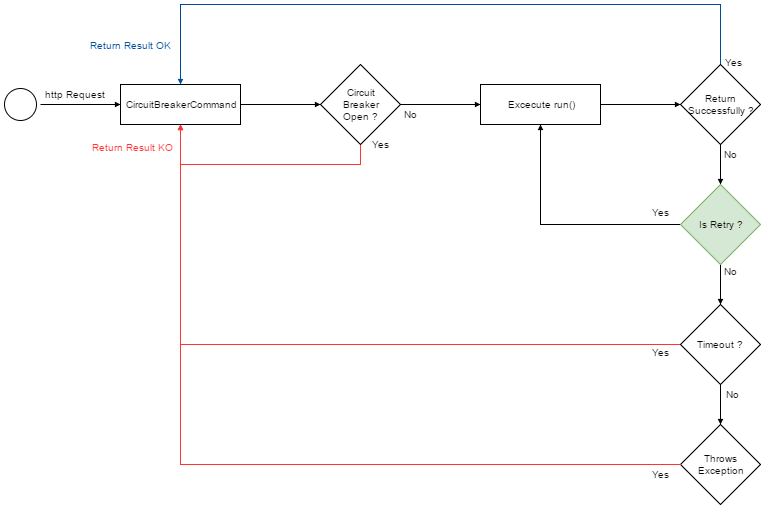

Using Retry pattern with circuit breaker pattern1 we will have this workflow:

1. “Circuit breaker pattern”, This content ↩